Walk The Runway: How Catwalks Transformed Through Fashion History

Designed by Sara Mouasher

When I first started scrolling through Pinterest for outfit inspiration in high school, I didn’t realize the peplum tops I loved so much had just graced the runway in a resurgence of 2000s staples. The peplum top was on countless autumn/winter 2023 collection catwalks, from Paco Rabanne to Christopher Kane to Bottega Veneta.

The peplum tops weren’t just a current trend, but a part of fashion runway history.

Long before the flashing cameras and elaborate settings of today, the fashion runway first hummed with the rhythm of models who turned walking into an art in late nineteenth-century Paris.

The origin of the fashion show can be traced back to English designer Charles Worth, who was the first to make the switch from mannequins to live models when showcasing his designs in Paris.

Worth, widely considered the “father of haute couture,” had his wife, Marie Augustine Vernet, as one of his original live fit models. Haute couture consisted of hand-constructed garments that were made to order for VIP clients, and it ruled fashion for roughly a century. Today, the Chambre Syndicale de la Haute Couture sets the criteria for a brand to qualify as haute couture.

In order to receive an invite to a couture show, or even walk into a couture salon, needed a flawless reputation in high society and relationships with the “right” type of people in the fashion world — exceeding just wealth.

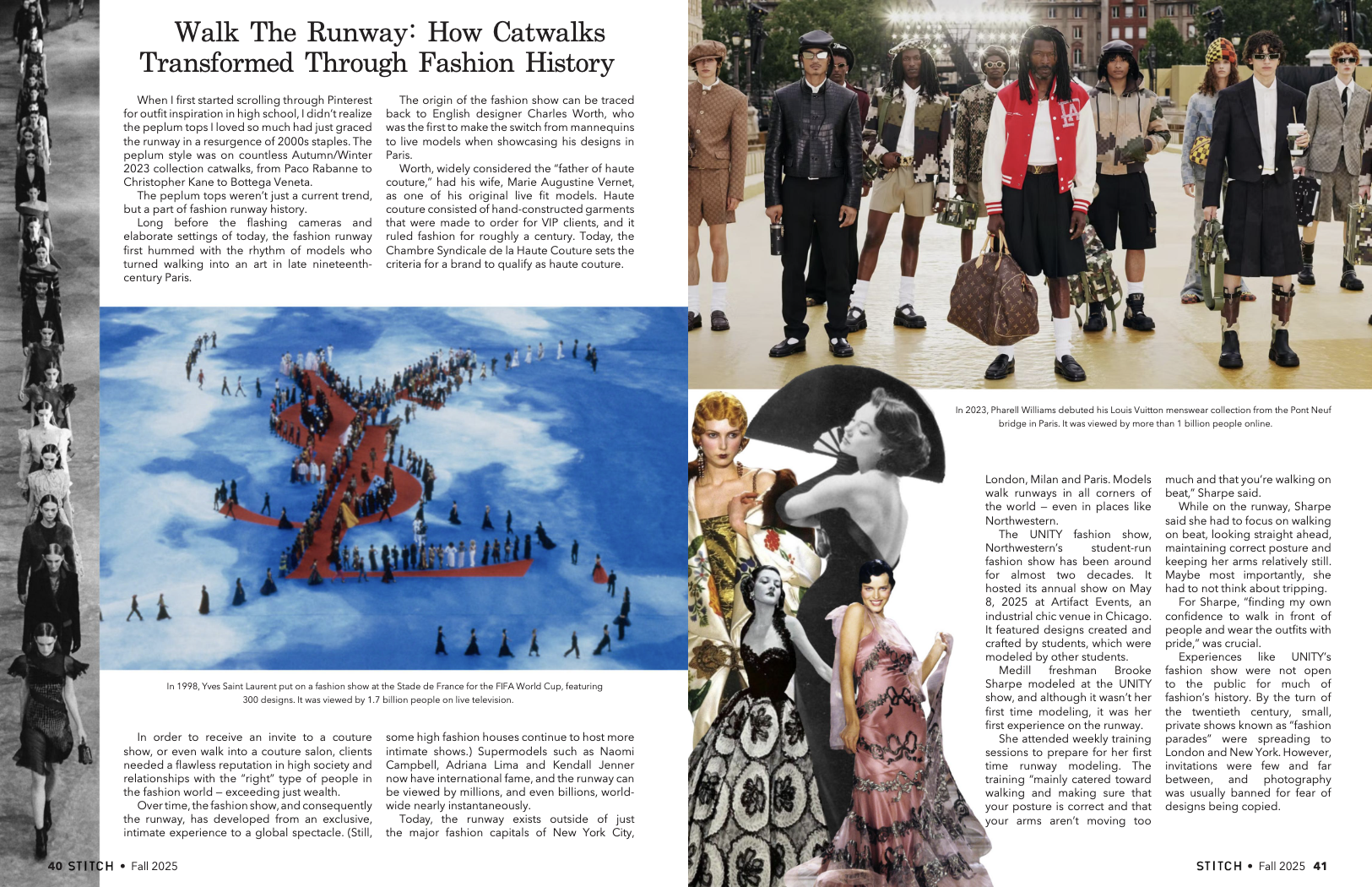

Over time, the fashion show, and consequently the runway, has developed from an exclusive, intimate experience to a global spectacle. (Still, some high fashion houses continue to host more intimate shows.) Supermodels such as Naomi Campbell, Adriana Lima and Kendall Jenner now have international fame, and the runway can be viewed by millions, and even billions, world-wide nearly instantaneously.

Today, the runway exists outside of just the major fashion capitals of New York City, London, Milan and Paris. Models walk runways in all corners of the world – even in places like Northwestern.

The UNITY fashion show, Northwestern’s student-run fashion show has been around for almost two decades. It hosted its annual show on May 8, 2025 at Artifact Events, a venue in Chicago. It featured designs created and crafted by students, which were modeled by other students.

Medill freshman Brooke Sharpe modeled at the UNITY show, and although it wasn’t her first time modeling, it was her first experience on the runway.

She attended weekly training sessions to prepare for her first time runway modeling. The training “mainly catered toward walking and making sure that your posture is correct and that your arms aren’t moving too much and that you’re walking on beat,” Sharpe said.

While on the runway, Sharpe said she had to focus on walking on beat, looking straight ahead, maintaining correct posture and keeping her arms relatively still. Maybe most importantly, she had to not think about tripping.

For Sharpe, “finding my own confidence to walk in front of people and wear the outfits with pride,” was crucial.

Experiences like UNITY’s fashion show were not open to the public for much of fashion’s history. By the turn of the twentieth century, small, private shows known as “fashion parades” were spreading to London and New York. However, invitations were few and far between, and photography was usually banned for fear of designs being copied.

Gradually, these fashion parades became theatrical spectacles. In 1901, English designer, Lady Duff Gordon, showcased her “Gowns of Emotion;” the showcase included live models, ethereal scenery, lighting, music and choreographed entrances and poses. This theatrical fashion show was one of the first to introduce the idea of a mainstream audience being able to see designs on a runway.

The traditional catwalk came from showcases in department stores in the early twentieth century, where large spaces could host middle-class shoppers —an audience that had not previously been invited to such presentations. From here, the modern catwalk became both prominent and popular.

As fashion shows became more theatrical, models’ stoic faces gave way to softer facial expressions that let their personalities peek through. Moreover, the rigid walking formation gave way to a rhythmic, powerful model walk to the beat of bass-heavy edm music.

Fashion shows continuously increased in scale and extravagance over the decades; the runway transformed into a production with sound effects, lighting, and elaborate staging. Runways soon left department stores as designers expanded their creativity with location and setting.

In 1965, French designer Pierre Balmain presented a collection in a wine cellar and in 1966, French-Spanish designer Paco Rabanne held a show at the Parisian cabaret Crazy Horse Saloon. These mid-century spectacles paved the way for 21st century shows beyond even Worth’s imagination. In 2007, German designer Karl Lagerfeld used the Great Wall of China as a runway for Fendi; in 2024, French-Italian designer Pierre Cardin’s show was held outdoors along the Seine in Paris.

Today, the runway has never been so within reach. French designer Thierry Mugler’s 1984 show was the first to allow people to buy tickets, opening the doors that had previously hidden the fashion world from the general public. Now, the public has access to runways from all over the world. Since the rise of the Internet, fashion bloggers have been able to stretch the audience even further. Textured fabrics, vivid colors and glittering details are captured in real time and posted online.

UNITY’s Modeling Director, Communication senior Jaida Hill, said that seeing designs on the runway is much better than seeing them on the mannequin.

Hill, who joined UNITY her sophomore year, directed the models for this year’s show. She said that above all else, she advised them to be confident.

She also designed a collection for the show, and as the models walked down the runway, Hill said her pieces finally all made sense.

“I’ve seen the pieces a thousand times because I worked on them all time, but then actually seeing it on the runway is a little bit different,” Hill said. “I feel like when I work on them, I would see them all the time so I’d be a lot less impressed by it. But then actually seeing it walk, I was like, ‘This is worth it.’”