Self-Obsession is in and Frida Kahlo is my Savior: Is Modern Vanity Deep?

Graphic by Carly Witteman.

“I paint self-portraits because I am so often alone, because I am the person I know best.”

Renowned Mexican painter and feminist icon Frida Kahlo answered this in response to why she is the sole subject in a third of her nearly 200 paintings. Being bedridden and isolated for significant periods of time due to disease and injury, Kahlo was “the subject to which she had greatest access,” as the Art Gallery of New South Wales puts it. The result of her “boredom and suffering” and the crude set up in her hospital room (a mirror placed directly above her bed and an easel mounted by her parents) would create one the greatest artists of the 20th century. But her art reveals more than just innovation or creative prowess: her focus on the self also provides prescient commentary on social media, stretching the truth and contemporary vanity.

If you scroll on Reddit (God forbid) or listen to Gen Xers long enough, you’re bound to encounter heaps of cynicism toward younger generations and the effects of widespread technology usage. You’ll hear something like, “Young people are full of narcissistic superficiality. They’re all obsessed with themselves and their social media. We're doomed.” The view that social media has allowed adolescents and millennials to become absent-minded solipsistic robots that underrepresent their struggles and promote their idealism is rampant. If this sounds harsh, just check out this HighSnobiety article where writer Aleks Eror labels certain social media addicts “infantile clowns…who rarely venture out of their bedrooms.” Yikes.

What can Frida Kahlo’s illustrious career contribute to conversations about modern vanity? For one, she often toyed with her identity throughout her life. Her self-portraits were a way to confess, connect and create. These three qualities are the same hallmarks of social media. Its initial draw was the ability for fellowship, networking and keeping up with friends. Now, it has all but become an industrial complex, pervading every corner of our lives and rewarding us for engagement.

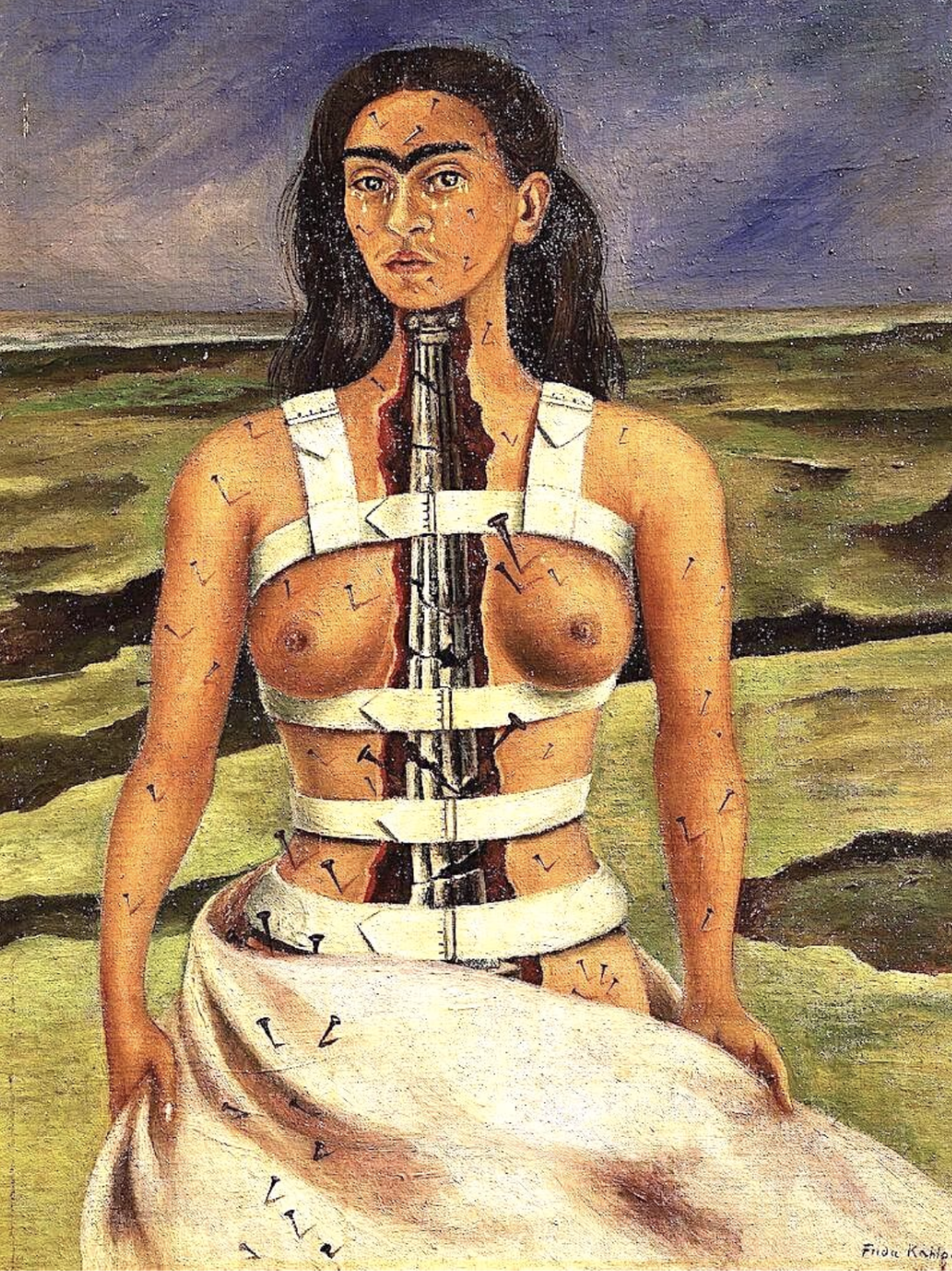

The Broken Column, 1944. Image courtesy of www.FridaKahlo.org. This piece references a tragic bus accident that permanently damaged Kahlo’s spine and left her in a body cast.

This growing reliance on media-sharing apps like Instagram, some believe, has greatly overstated the importance we place on the self, and the self that is most desirable and digestible, at that. So politicians, TikTok podcasters and general cynics condemn our generation to mass vapidity and obnoxiousness because we only approve photos from our “good side,” or do fit checks in public, or post a quasi-effortless #photodump or continuously retake photos on an app imploring us to “BeReal.” My question is, is there a root to this seemingly surface-level self-obsession?

Kahlo’s “self-obsession” enabled her to comment on her unique experience—a way to “communicate her pain… as well as her joy.” The product of her isolation was tangible and intimate introspection, with her paintings often covering subjects like her disability, the infertility the former brought on and womanhood in surrealist tones. This puts into perspective the American “Loneliness Epidemic” exacerbated by Covid-19 isolation, negative effects of ever-growing hyper-individualism in the west and how they may affect the ways in which we use social media.

Maybe we’re not completely vain. In our recent shutdown of all things real-life communication, social media became the real world. Creators now use sites as a visual diary or proof of existence. They use it as a way to investigate their identity and format their legacy. This full control over one’s selfhood that Kahlo employed may be one of the reasons why being an “influencer” has become a more and more attractive profession. It does not exempt you from criticism or cancellation, but it does allow you to craft yourself, to curate your perception.

With users’... propensity to embellish (let’s call it) creators are often seen as shallow. However, Kahlo did the same to enhance her artistic identity. Her many posed self-portraits and calculated embellishments were a way to create herself. For example, Kahlo claimed she was born in 1910, the year of the Mexican Revolution, despite actually being born in 1907. This was not for vanity’s sake; rather, it was “a statement of identification: she was a ‘child of the revolution’.” Kahlo is of central European and Mestiza descent, but adopted the “Latinized” version of her original German name Freida to better fit her self-perception and Mexican identity. Kahlo’s photographer friend, Lola Álvarez Bravo, once said that “Frida is the only person I know, who by their own will, created their own life. She is the only person who gave birth to herself.” This seems to be the draw of social media that so perturbs its critics: the opportunity for self-invention.

Of course there is something to be said about the negative mental and social impact of obsessively creating and distributing a contrived persona—what with internet celebs garnering profit off of unattainable beauty standards, consistently racking up screen times longer than the MCAT and being in danger of becoming more an avatar than a real person. I am the last person to say that social media and its willfully ingenuine users with millions of impressionable followers should be absolved of their crimes. I’m also not trying to say that the Snapchat puppy filter was the most thought-provoking artistic contribution of the 21st century. I don’t wish to justify the “Black Mirror” episode we’re stuck in: I simply want to explain it.

It should be noted just how destructive self-invention can be. Frida Kahlo, as I mentioned, was part Mestiza, her mother coming from the indigenous group Purépecha in the Mexican state of Michoacán. Though in the U.S. Kahlo is adored for her proud portrayal of “Indigenismo,” many indigenous peoples from the groups she picked and chose from (namely the Zapotec) find her culpable of attempts to homogenize, sanitize and trivialize the distinct native peoples of Mexico. Take this Hyperallergic article and this Twitter thread on Frida Kahlo’s impact from indigenous perspectives. The manipulation of self can breed shortsightedness and encroach upon the identities that others have crafted, passed down and embraced. Take the modern equivalent that is Halloween costume appropriation or Ariana Grande switching races every couple years.

Frida Kahlo in traditional Tehuana garb. Image courtesy of Vogue magazine.

Frida Kahlo and her self-exploration and curation illustrate how focusing on oneself can be both a fruitful and damaging endeavor. Self-obsession is not an immediate deterrent of depth. You are the center of your observable universe. It will always seem like everything expands around you. Being careless with self-cultivation, however, can distort others’ sense of self. Nevertheless, introspection is a necessary tool for actualization. For Frida Kahlo, this manifested in creating a body of self-portraits and a cohesive persona. For us, it can mean a respite from loneliness or treating social media like a journal or logging every single emotion you’ve literally ever experienced in your camera roll.