More Than Skin Deep

A look at three Northwestern students’ tattoo history shows how we modify our bodies to reflect our losses, our connections, our identities and so much more.

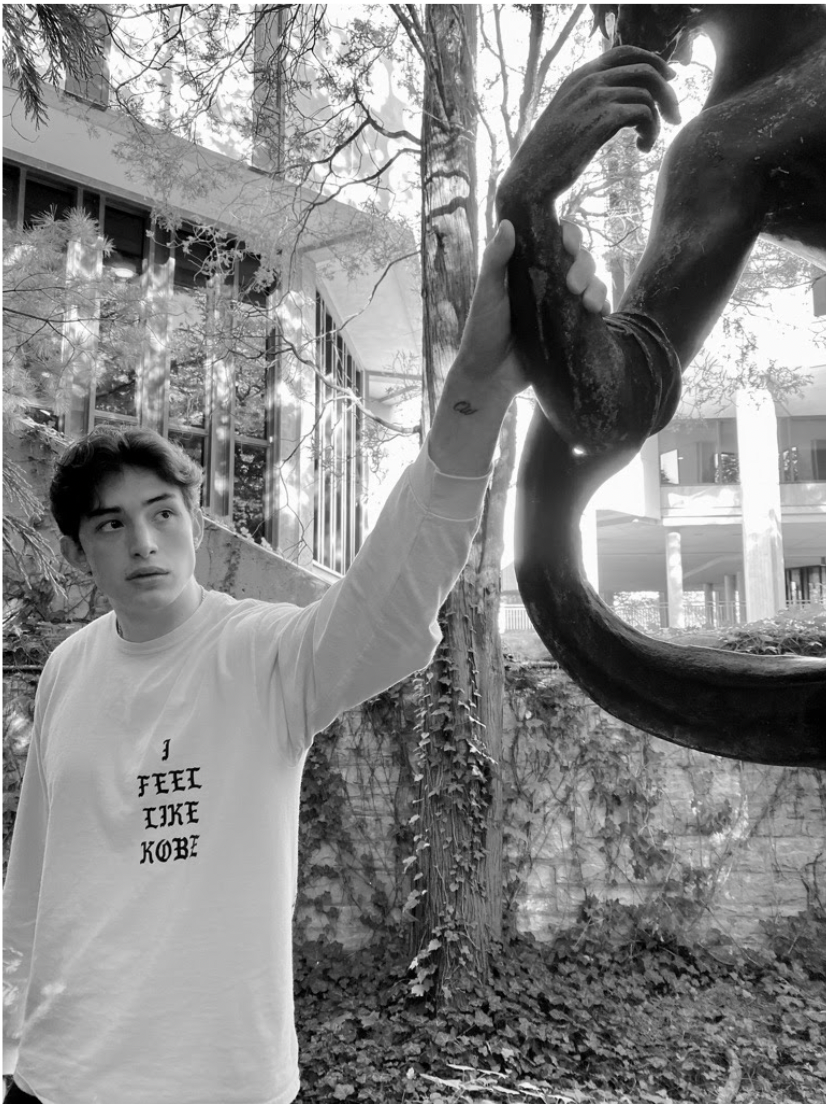

George Javitch

George Javitch, a senior on the pre-medicine track, said his family strongly disapproves of tattoos. He jokes that while he couldn’t quote the scripture, he was sure somewhere in the Bible, there is something that has come to be used as a direction to avoid tattooing our bodies.

During Javitch’s freshman year, he found out his close friend died while being hazed by a frat. Javitch and his friends decided to tattoo the initials of their friend who passed away on their wrists. The initials face inwards, which was abnormal according to the tattoo artist. The tattoo reminds Javitch of his friend’s life and their time together whenever he looks at it. You can feel your heartbeat in your wrist, which makes it feel close to his heart. Javitch said he didn’t care if his parents or family members disapproved of tattoos, and given the context of this particular tattoo, they expressed no objection.

Often, people’s tattoos relate to their home or family. Javitch expects that after his girlfriend gives birth to their daughter, his next tattoo will honor her with something related to the moon. Becoming a father as a 21-year-old has certainly altered the course of Javitch’s last two years of college. He reflected on his changing perceptions of his body, as well as women’s bodies, as he moved from having casual sex and college relationships to supporting his pregnant girlfriend, and now preparing for the birth of their child.

Grace Shin

Grace Shin always knew she wanted tattoos. Growing up in an “overwhelmingly white and conservative” town in New Jersey and transitioning to a primarily white institution, Shin reflected on never feeling conventionally beautiful. As an East Asian woman with a darker complexion, she remembers being questioned by her family for the darker color of her skin. Shin explained that she received the message that she was not meant to feel comfortable in her own skin from a young age.

After struggling with body image issues and trauma, in addition to her experience with racism, her first tattoo was for her own healing with her body. It was the first major decision she got to make regarding her body, and she felt the power to reclaim it. Shin has also found love for art, and wanted to add art to her body in the hopes it would increase her love for it, which it has.

Something that Shin said to me that will stick with me forever (no pun intended) is that we have no power over our height, our hair color and texture or our skin color, but tattoos allow us to take power back over the control of our bodies. Her first tattoo sits on her ribcage: it’s an image of Jupiter. Jupiter represents optimism and power, and it reminds Shin that compared to the universe we are tiny and impermanent. Remembering this helps Shin put herself into context when she is struggling with anything.

Shin now has over 10 tattoos. She spoke with me about the word “forward” on her wrist, which represents her reflection on the best piece of advice she was ever given: even when we all feel stuck, the only direction is forward. She also has a lip tattoo of the word “trouble,” because, duh.

Her most recent tattoo, which Shin referred to as “her,” is an image of a woman's legs diving into water in the center of her chest. This tattoo wasn’t planned — it was exciting, and freeing, and took place at a tattoo shop in Chicago without an appointment at 2 a.m. Shin was brimming with joy as she discussed her most recent tattoo.

I asked her if she feels this confident after each of her tattoos. She said yes. Even the tattoos that at times she questions, such as the “forward” which she felt was cheesy immediately after getting it despite its deep meaning, or Jupiter, which a boy thought was an Easter egg, have taught her about loving and accepting her body. Learning to love your body as it is, for the pieces of it that change and the pieces that don’t, is central to truly loving oneself, which is Shin’s goal and practice.

Anonymous

This next student discussed the pressure to be sophisticated in order to be taken seriously, to take up space, to play and embrace our inner silliness and remember ourselves in the context of what small specks we are in the course of life’s history.

Her tattoos are a statement of her existence as something other than what was expected of her. Rebellion against her parents, who had convinced her she actually really liked the preppy clothes she wore everyday to her West Village high school in New York City. Rebellion against the porcelain image she had always felt attached to her blondeness.

Her first tattoo is a lightly drawn woman on her forearm that was taken from one of her favorite artists. While she loves this tattoo, she hates that her parents approve of its inherent sophistication.

Her second tattoo, on the other hand, her parents hate. She giggled. It's a white cat with a black mask on that reminds her of “Fantastic Mr. Fox,” which was the tattoo she intially wanted before learning about Roald Dahl’s history of anti-semitism. She got this tattoo just a week or so after she met her current boyfriend; she remembers inviting and then uninviting him from her appointment. She wanted her tattoos to speak to her lived experience and be unattached from any and all other people. As someone who has always felt the need to put effort into taking up space for fear she would otherwise blend into the background, she wants the space of her body to exist just for her. No tattoo memories with boyfriends with undetermined futures.

She recognizes her boyfriend, who met her after she started getting tattoos, must have a different image of her. We spent a long time reflecting on this ability for tattoos to break into, or alter, our natural self images. How can something simultaneously be so permanent and attached to us, yet so surfacelevel that we do not always remember or notice it ourselves?

Jacqui Touchet

Jacqui Touchet is one one of my best friends, and we began talking about tattoos standing in my kitchen, joking about our shared desire to randomly rip things from our bodies during panic attacks. Which we laughed about. We often find ourselves sharing a bond of bodily experiences, struggles with perception and a general fear of our own hilariously deranged thoughts.

Touchet strives to express themself externally in many ways — if you have seen them around campus you will know of their notoriously creative fashion choices. As Touchet has continued to grow into themself, they have found a desire to detach their inner and external selves from the emphasis that society places on our bodies and appearance. Tattoos exist largely genderlessly and provide this freedom.

Touchet’s first tattoo was of a milk bottle, located on their lower back. Growing up with a “hippy-dippy” mother in Dallas, they were never given formula as a substitute for their mother’s breast milk. When she stopped producing enough to nourish Touchet, Touchet was given their aunt’s break milk — Touchet and their cousin had been born within weeks of each other. Touchet’s relationship with their cousin was closer than typical cousins, and they began to call themselves “milk sisters,” leading to their decision to get matching milk bottle tattoos to remind themselves of their deep connection to one another.

Struggling with OCD has caused anxiety for Touchet in terms of the decision to get tattoos. Locating the milk bottle on their upper back allows Touchet to feel connected to their cousin without forcing them to look at the tattoo every day and develop an urge to remove it. However, the next tattoo Touchet is planning is meant to explicitly challenge the symmetry OCD they struggle with as a mechanism of proving to themself that a lack of symmetry can be beautiful and positive. The tattoo will be located on their chest between their breasts and will be an asymmetrical butterfly.